Celebrating Ruby Dee's 100th Birthday

Honoring the magic of the one of a kind actor, writer, activist, and star.

Black Film Archive is a living register of Black film, this Substack is its blog. If you want to support Black Film Archive, visit our new shop. Thank you for your support.

The first visual spell I ever saw Ruby Dee cast was in 1961's A Raisin in the Sun. Dee's on-screen magic defies the stereotypical cinematic iconography of Black womanhood I grew to expect as a young movie lover. Instead, Dee delivered a nuanced and forceful enchantment as Ruth in the film adaptation of Lorraine Hansberry's masterwork. Here, she is a grounded foil to Sidney Poitier's explosive presence. Her performance — rooted in reality and above it — was planted in my heart and mind. Dee, who originated the role of Ruth on Broadway, brought her all to the screen adaptation, and my lifelong admiration followed.

Disruption was a spell she continued to cast on stage, screen, and beyond.

Ruby Ann Wallace was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on October 27, 1922. 1Her family migrated from Cleveland to 7th Avenue and 134th Street in New York City's Harlem when she was a newborn. Shaped by Harlem's role as the nexus of Black political thought and artistic expression, Ruby Dee found her early artistic vision by attending demonstrations with her family, writing poetry, and learning from her mother.

“In a sense, I grew up in the drama of the times, listening to the speeches, watching the pickets, and hearing people in the trucks up and down Seventh Avenue protesting this or announcing a meeting and that kind of thing. All of that, I think, is fuel to the imagination of a child,” Dee recalls in a 2001 interview.

During her enrollment at Hunter College, Dee found early success with her first great love, acting. While a student, she started taking classes at the American Negro Theatre with her peers Clarice Taylor, Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Helen Martin, and its founder, Frederick O'Neal. In 1940, the actress made her stage debut in the Negro Theatre's first production, On Strivers Row, as Cobrina. With the American Negro Theatre, Dee could hone and shape her craft alongside the best actors working. Her first starring role in 3 is a Family made way for her being a star player in the Negro Theatre's repertoire.

As Dee tells it, nothing prepared her for the success that would come for her and her peers as Black stars. In the 1940s, there were opportunities for their world to integrate into arenas previously unreachable. The Negro Theatre's Anna Lucasta hit the big time with a run on Broadway and effectively ended the Theatre as a fertile ground for Black actors to craft their talent among themselves. With these Black actors honing their craft in a world of their design in the American Negro Theatre, a generation of talent, like Dee, was able to see their dreams realized.

"We had not prepared to be this tremendous success. We got integrated… I think the American Negro Theatre was as vital a part of the theater movement as anything in this country. But after Anna Lucasta, it became "Oh, do you want to get to Broadway?" Dee says in a 2001 interview.

And Broadway she went. In 1944, Ruby Dee made her debut in the short-lived South Pacific, starring Canada Lee. She replaced her Negro Theatre peer Hilda Simms as Anna in Broadway's 1944 Anna Lucasta. Her 1940s were filled with a run of significant productions on the world's largest stage, including a substantial role in 1946's Jeb alongside Ossie Davis.

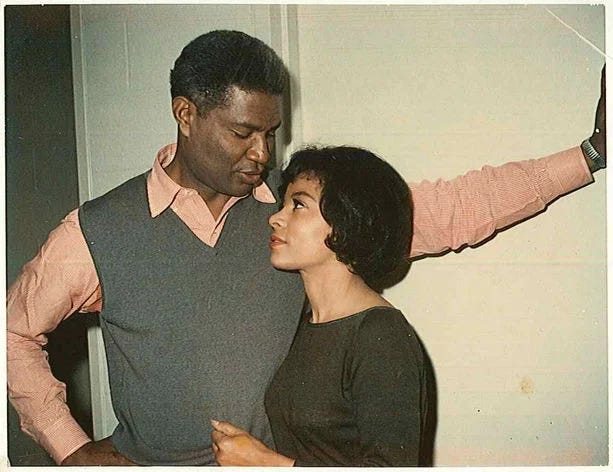

In 1946's majority Black-cast Jeb, Dee played the small-town partner awaiting Ossie Davis's black soldier character's arrival back home from the Pacific War. It was during this play that Davis and Dee's lifelong partnership began. The two were married in 1948 and moved to Hollywood in 1949.

Upon moving to Los Angeles, the newly formed couple remained in community with their Black stage acting peers also in transition to screen — namely Sidney Poitier and Fred O'Neal— and were met with work quickly. They felt a duty to be a tribute to their race, being among some of the first Black actors permitted to work in Hollywood steadily.

"I remember going to Hollywood and feeling intimated, a little inferior… there were no African Americans in the technical areas; I didn't see any black cameramen or grips or electricians. No makeup artists. No black people in wardrobe," Dee reflects in a 2004 interview.

Though Ruby Dee's first film appearance was in 1946's That Man of Mine, her first starring turn was in the 1950s Jackie Robinson Story as the baller's wife, Rachel Robinson, opposite the famed player himself. With W.C. Handy's biopic St. Louis Blues, the effecting coming-of-age drama Take a Giant Step, and the 1958 integrationist drama Edge of the City, co-starring Poitier, Dee was able to showcase the full range of her acting chops on screen. Her 1950s screen run cemented her legacy as an enduring Black star.

Dee returned to Broadway with 1959’s A Raisin in the Sun with her frequent costar, Poitier, to critical acclaim. When Poitier left the role, Ossie Davis stepped in to finish the shows run before being reunited with Poitier in the 1961 film.

“I think on the stage you're exploring the limits of yourself. How loud and how strong and how big and how wide is the human entity? How much are we like giants and kings? Can we touch the sky in the arts? In film, I think we're taking pictures of thoughts—and that's intriguing,” Dee notes.

Discussing Ruby Dee's life without activism is not to see her life at all. Early on, Dee saw the importance of dedicating a life to the advancement of all people. In the overlapping world of politics and celebrity, Ruby Dee saw an opportunity to use her celebrity as a way to give voice to movements.

"There was a time of giving birth and of getting born into a wider concept of ourselves as actors, and into a heightened sense of art and the struggle as inseparable bedmates," Dee states.

In the era of McCarthyism, Dee and Davis disrupted the idea that the only way to remain working in Hollywood was to be silenced by fear. The activist couple protested the execution of suspected communists. With their ongoing organizing work with the NAACP, Martin Luther King, Jr, Malcolm X2, and numerous other civil rights groups, Dee and Davis saw artistic expression rooted in struggle as one that could free themselves and others. Their lives were spent fighting justice for others around the globe on stage, on screen, and in every political arena.

“I tell you what our total life experience has been: a sense that, no matter what, we were not just actors. We were black performers, black people. We belong to a certain constituency. I know who I am; I belong somewhere, and these are my people. That idea of "my people, my people" has always been a part of us,” Dee says.

Dee and Davis were partners in life and work.3 Their marriage birthed countless projects — where they collaborated on stage, screen, and television to create a prolific rolodex of media they felt best represented Black life. Notably, Purlie Victorious (play and film), Countdown at Kusini (1976)4, and With Ossie and Ruby PBS children series, and Davis’s directorial work Black Girl (1972).

Dee managed to stay current to numerous audiences by continuing to work with emerging directors and fresh collaborators. In the 1960s, she appeared on the soap opera Guiding Light as a part of one of the first Black couples featured regularly on television; in 1964, she won a Daytime Emmy for her role in Nurses; in 1965 Dee became the first Black woman to appear in a major role in a Shakespearean play with King Lear. In 1972 she co-starred in Sidney Poitier's directorial debut Buck and the Preacher; returned to stage in her Obie-award winning performance in The Wedding Band; she developed her first musical Take It From The Top in 1979; and performed in countless public television productions. In 1989 Dee and Davis were introduced to a new generation of moviegoers with Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing and, later, Jungle Fever (1991). In 1992, Dee narrated Marlon Riggs’ transcendent Color Adjustment. In 2007, she garnered late-life triumph in her Oscar-nominated performance in American Gangster.

“My life got filled with possibilities, and filled with the challenges to make those possibilities real… [I would say,] ‘Here’s another door. Oh this is my door. Oh here I go!’ And then gradually find all kinds of doors begin to open,” Dee notes in a 2003 interview while reflecting on her career.

What is the magic in Ruby Dee’s craft? She knew the depth of her gifts and the power of the credibility she brought to her roles. By some miracle, Dee was able to give us a wealth of media to see her cast wonder on us all. Ruby Dee is an enduring performer and one of the only Black women performers who garnered enough support and longevity to tell us who she was and what she did it for. Long may she reign in our hearts and minds.

Happy birthday, Ruby Dee!

P.S. - This spooky season, check out the new horror genre page.

Her date of her birth—as with many people born pre-Social Security— is contested. I am basing this date off of the obits that were published in her passing.

Ossie Davis delivered the eulogy and Malcolm X’s funeral and Martin Luther King’s.

I am deeply fascinated by this quote of hers: “Do I take that job when the kids are in school and leave him with the kids, maybe get one of our mothers to pitch in, or hire somebody?-I felt very guilty. Some job offers came that I couldn't accept. I didn't go to England, I didn't go to Hollywood. When we talked about it, he didn't say, "Oh, Ruby, go on. I'll take care of things." Had he done that, I might have done some other things.” One can’t help but wonder if she would direct or have more opportunities to write if she had even support in home life.

Notably out of print

This read is so beautiful, I’m so proud of our wonderful and amazing heritage 🙏🏽❤️

Aahhh - Ruby Dee - certainly one of few eminently watchable, and always compellingly believable performers, in all three media - stage, film and TV. She left high marks to be striven for by anyone.