There's Something About Harry Belafonte

Remembering the Music, Stage and Screen Titan; 1927 - 2023

Harry Belafonte’s films currently streaming can be viewed on Black Film Archive here.

During racial segregation1 in the United States, Black artists were forced to make an impossible choice of lasting consequence: play by the social order —and rigid ideas of Black representation— offered or go without work. Harry Belafonte—the man, and artist who dominated stage, screen, and music charts—refused. His ascent to the upper echelons of entertainment — Black or otherwise— is integrally linked to this act of refusal and his continued interrogation of Black life through acting, producing, stage performance, and top-charting musical numbers. At the core of his being was an act of continued questioning as an act of continual care.

Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. (b. March 1, 1927, d. April 26, 2023) was born into a Harlem working-class, West Indian family. Belafonte learned early on that the shared vulnerabilities coming from being poor—and community care—were the way of being. As the first in his family to hold U.S. citizenship, his childhood was clouded by the forced anonymity that comes from having immigrant parents without citizenship. His childhood unfolding across Harlem apartments that hosted numbers games and Jamaican family homes. Belafonte remembers, “My mother had come to the conclusion that there was no deal she could make with God or the Devil to ease the sting of poverty. The best she could hope for was to instill strong goals and values in me.” With a link to community from Harlem’s underground, accompanying his mother to Marcus Garvey organizing meetings, and the growing labor battles in Jamaica2, Belafonte’s values were cemented early on with visions of collective self-help. “Raising ourselves from poverty wasn't enough.” His mother told him, “We would have to help others.”

After dropping out of high school3 and a short stint of odd jobs, Belafonte joined the segregated Navy in 1944. Inspired by seeing Rex Ingram’s4 heroic punching of a Nazi in the 1943 picture Sahara, a young Belafonte felt the armed forces could offer him an avenue to fight fascism. Quickly, he learned from his fellow segregated troops about the dynamic Black rage— rage against white supremacy in the army and outside of it. He found camaraderie among his peers as they expanded his knowledge of class and race by introducing him to Du Bois and the depth of the ‘Negro problem’ in America.

Belafonte stumbled into the rich world of acting by chance. Freshly settling into civilian life after being discharged from the military, he worked as a janitor in the buildings his stepfather serviced. When a tenant, Clarice Taylor5, tipped him with tickets to a play about Black servicemen at the American Negro Theatre, his fate was sealed.

“I knew these characters. I knew the problems they were talking about. That play didn't just speak to me. It mesmerized me. This was a whole new world—an exhilarating world,” Belafonte recalls.

American Negro Theatre (ANT), where he worked as a stagehand before becoming a repertoire player, became a beacon of progress for Belafonte. The Theatre’s work portraying Black life as it was lived and nurturing community talent became the ethos of the starred performer’s career. The cultural and political scene the young Belafonte grew up in shaped his early excitement for the craft and molded what be believed to be possible for the form. The Theatre unlocked new possibilities for his life and is also where Harry met Sidney.6

“Sidney and I were soul mates—separated at birth, or so it seemed. Our setbacks and hurts, hopes and ambitions were so parallel that each of us knew what the other would say-about almost anything,” Belafonte recalls.

Besting each other for roles at the Theatre and throughout their careers, finding kinship in their deeply similar backgrounds, and challenging each other’s ideology, Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier were each other’s first true, lifelong friend.

Belafonte’s involvement at ANT also introduced him to his lifelong hero, Paul Robeson, in 1946. While performing in his first lead stage role in “Juno” as a radical Irish farmer, Robeson stopped by to extend his appreciation to Belafonte and crew. From that brief conversation with Robeson and the mentorship that followed, Belafonte saw everything he wanted to be: an artist with unshakable integrity that radiates love in word and deed. The role of the actor, Belafonte realized as he followed the path Robeson set, must be one that uses their platform to do all they can for their community.

“With awe and admiration, I followed everything Robeson laid and did. To be such a consummate artist and at the same time speak out against injustice—there could be no higher platform than the one to which he'd ascended,” Belafonte said in reflection of meeting Robeson.

With performance, Belafonte channeled his righteous anger into an artistic vision that moved Black artistic and political life forward. He sustained that radical vision by only accepting roles that spoke to his whole embodiment and dedicating his life—artistically and beyond— to activism.

Initially turning to musical performance as a Jazz performer to pay for acting classes, the crooner immersed himself fully into folk music by 1951. The form became his signature as he ascended to the heights of “Calypso King”7 in the 1950s. The songster’s calypso and labor-infused musical repertoire celebrates the rich history of the griot— the narrators who use call-and-response musical remembrances passed down through generations to help us recall, reflect, and reignite history. As one of America’s most insurrectionary folk singers, he ignited America’s Caribbean music movement of the 1950s and a widely-celebrated way for Black people to reclaim our history through song and expose racial inequality.

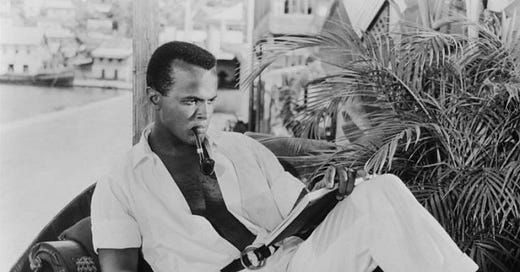

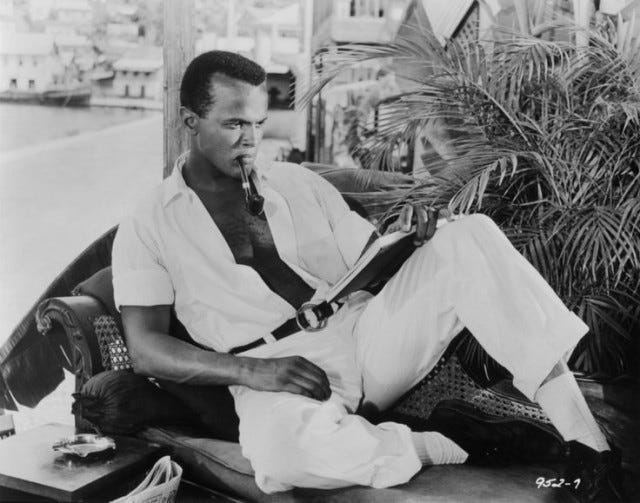

Hollywood placed its bets that the charismatic spell Belafonte cast on audiences on stage could be translated to the screen. Soon, the performer became Hollywood’s first leading Black star—with a screen debut in 1953’s “Bright Road” alongside his four-time screen partner, Dorothy Dandridge. In 1956’s “Carmen Jones,” the pair reunited. Belafonte was the sensual romeo to Dandridge’s sexual juliet. Their intoxicatingly vibrant and lustful screen personas in “Carmen Jones” reimagined Black cinematic possibility—in a way only they could.

With 1954’s “John Murray Anderson's Almanac,” Belafonte became the first Black actor to win a Tony.

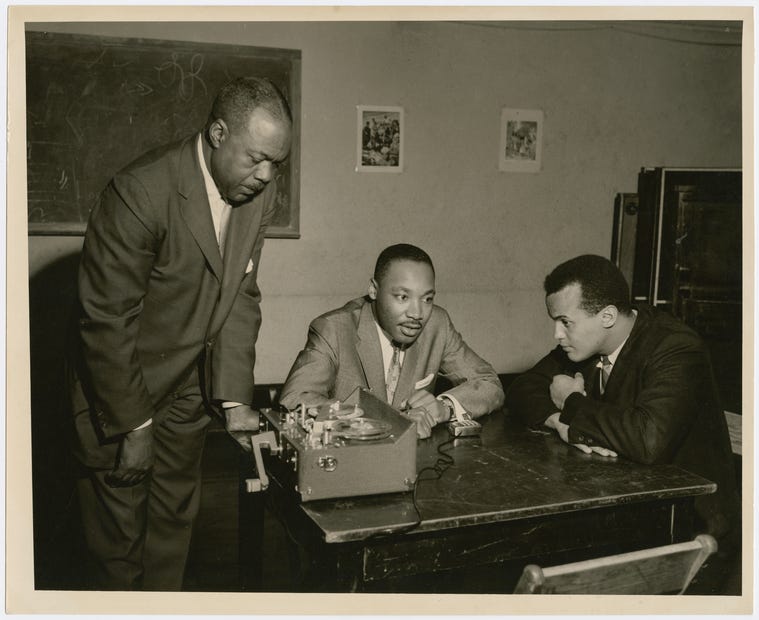

As his public persona grew, so did his commitment to honor his hero Paul Robeson by using his celebrity for the cause. He befriended and became a staunch supporter of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and used his earnings and influence—as the highest paid Black performer— to fund freedom rides, bail for Dr. King and his organizers, the March on Washington, and support Dr. King’s family after his assassination among countless other things.

Hollywood’s desire to cast Belafonte and Poitier solely in the integrationist pictures, meant that Belafonte— who became one of Hollywood’s earliest Black producers with the revolutionary film noir “Odds Against Tomorrow”—turned his focus to the promise of television. For 1960’s “Tonight with Belafonte", the performer became the first Black man to win an Emmy. His promising television career, which included an infamous run as guest host for “The Tonight Show” in 1968, was halted at every turn by sponsors and producers fearful of his vision of racial progress on screen8.

Belafonte’s mark on stage, screen, and sound can be encapsulated by an idea he never stopped believing in: art is a tool of social change, a way to galvanize a public to urgent action, and soothe when action isn’t immediately possible. Mirroring the hopes of Paul Robeson, a performer willing to sacrifice his career for the cause, meant that radical ideas were at the heart of every performance Belafonte courageously gave.

Hero feels like a word too insignificant for Belafonte— a principled, innovative star— who was never seduced by the siren song of silence or the plush comforts of fame in an era when representation was seen as the only possible progress, but, for now, hero must do.

Watch every Harry Belafonte film on Black Film Archive here.

Arguably, this choice continues.

Belafonte lived in Kingston, Jamaica from 1935 until 1940, with his mother joining him in 1936 as the Great Depression ravaged on. When he returned to New York in 1940, he was 13.

He dropped out after his first semester of 9th grade.

Black character actor. Plays De Lawd in Green Pastures.

Legendary Black stage star. Perhaps best known to modern audiences as Aunt Emma on Sanford and Son or Anna Huxtable on the Cosby Show.

He notably hated this term.

His deal to produce more tv specials like his Emmy award winning one was canceled because he refused to stop showing Black and white performers together on screen.

Icon. Legend. Words fail to describe this GREAT. May he rest in peace.

He and Dandridge were, possibly, the most impossibly beautiful pair to ever grace celluloid in Carmen Jones.

Rest in peace, sir.