Watching Zeinabu irene Davis at the End of the World

On “A Powerful Thang,” “Compensation,” resurrection, and reinvention.

This interview series and the ongoing maintenance of Black Film Archive is made possible by the paid subscribers. Thank you, all. If you like work like this, consider subscribing.

I am often reflecting on Ntozake Shange’s choreopoem “For colored girls who have considered suicide, when the rainbow is enuf.” In the first chapter of the infamous work she proclaims:

somebody/anybody

sing a black girl's song

bring her out

to know herself

to know you

but sing her rhythms

carin/struggle/hard times

sing her song of life

she's been dead so long

Cinema has a way to render Black womanhood invisible in its active suppression of our fullness– our rhythms, carin, struggle, hard times, songs of life— that animate all we touch, are, and can be. Black women filmmakers, with a deft hand, take the impetus of Shange’s choreopoem and bring “an oppositional gaze,”1 as bell hooks famously named. hooks reminds us that, at its essence, media is a “system of knowledge and power reproducing and maintaining white supremacy.” Within our gaze, film is given new modes of understanding and image construction.

Zeinabu irene Davis is one of cinema’s independent architects that mirror the fullness that Shange and hooks promise. Davis’s work is best expressed in her own words: “I am trying to create a visual language that is reflective of the African-American female experience. So I am very specifically trying to do projects which are based on the lives of women that I know. I am trying to not necessarily tell a story in strict narrative style, but trying to take some chances, take some risks in telling the story to get across the everyday experiences of Black women’s lives.”2

Zeinabu irene Davis began her career while studying pre-law at Brown University. While at Brown she was an intern at WSBE-TV, working on “Shades,” a Black-interest public affairs program hosted by Gini Booth. Her and film found each other as she was studying abroad in Kenya and began working with Ngugi wa Thiong’o3 in 1981 as a rear projectionist for a production of his play. Eventually they agreed to work on a film together. When government censorship shut the play down and Davis returned to America before formally working on the proposed film, the impulse to create and the Africana spirit remained with her. She received her M.A. in Africana Studies and M.F.A in Film / Television Production from UCLA. Zeinabu is a part of the “LA Rebellion” —a cohort of Black filmmakers at UCLA who’s commitment to Black image and craft-making pushes beyond the presumption of film’s white, hierarchal, and aesthetic framework4 with a focus on Black family, life, love, and liberation.

Davis’s “Wimmin with a Mission” productions banner encapsulates the spirit of her life’s creations, with a mission to present characters, themes, and scenarios far from Tinseltown’s definitions of inherent Black inferiority and form. The spirited director creates worlds of spiritual and emotional transformation, rending the world anew with her considered gaze.

In Davis’s 1991 short “A Powerful Thang”, a couple is anticipating their first sexual experience. As the day’s doldrums drag on, the anticipation becomes its own art form and explosion before the lovers —a single mother returning to dating and a jazz musician— find their own safe sex groove in the sacredness of Black love and intimacy.

With “Cycles" (1989) Davis tells the story of an anxious woman awaiting her overdue period. In this intimate short, the waiting woman cleans her house and body and performs purification rituals. The film combines music and dreams to tell a story uniquely for Black women.

Watching Zeinabu irene Davis’s considered and impassioned work at the end of this world5 reminds us that art can guide us to somewhere anew.

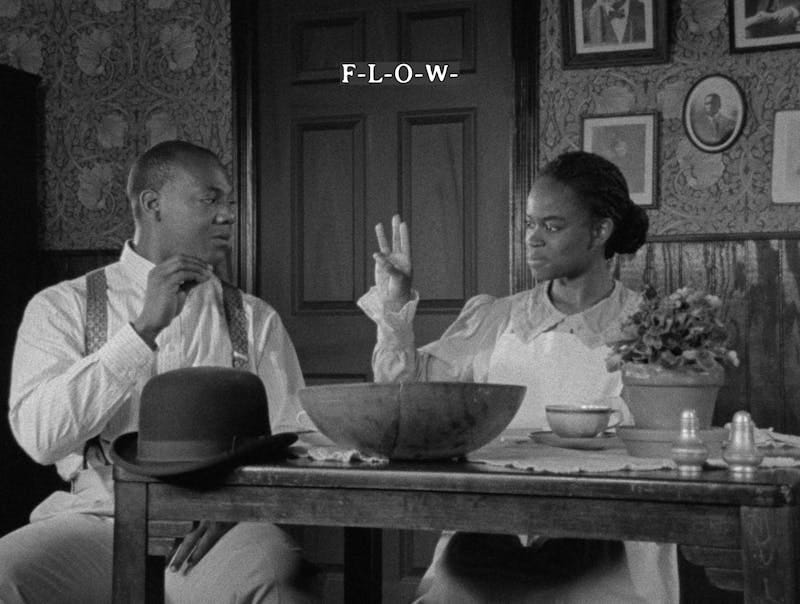

The legendary director joined me for a quick chat in celebration of the theatrical release of “Compensation.”6 The 1999 debut feature from Davis weaves together two sets of Chicago lovers—beautifully played by John Earl Jelks and Michelle A. Banks— featuring a deaf woman and hearing man, who face the edge of death from tuberculosis in the early 1900s and HIV/AIDS in the 1990s. Incorporating sign language, silent film techniques, and archival photography, “Compensation” is a student of the cyclical nature of love, life, and the abundance of Black archival possibility.

The innovative film, which played at Sundance in 2000, was relegated to the specialized screening market after a negative review prevented it from the full-bodied theatrical release it deserved. At the center of the film’s genius is Davis’s ability to not use lack—of funds and resources— as a detriment to her creative process but a spirit to carry on and sing a Black girl’s song.

In this new release of “Compensation,” as Davis explains in detail below, the film is not simply a restoration but uses technology’s advancement to highlight the form and techniques that were always at the heart of the film; but they are now rejuvenated. With considered intimacy of our history, love, cinematic language, and experimental form, “Compensation,” in its new form and in its past release, is genuinely one of the greatest films of all time.

Maya S. Cade: I want to begin our conversation with discussing how [the re-release of “Compensation”] happened. I know that Women Make Movies had the film circulating for many years. And then it kind of felt like the world cracked open for you in the last few years. So can you tell me a little bit about how that feels and how that happened?

Zeinabu irene Davis: Okay, well, it feels great. That's an easy answer right there. It happened primarily, I think, just the stars lined up. Ashley Clark programmed it as part of the Black 90s series at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Richard Brody actually reviewed the film along with “Sankofa” and “Daughters of the Dust” and he just fell in love with the film and kind of kept writing about it. Ashley moved from Brooklyn Academy Music over to Criterion and so the ball got rolling… [Criterion] picked it up in 2020 right at the beginning of the pandemic. [The] restoration/rejuvenation started pretty much last year and we've been kind of going strong ever since then.

MC: Something I'm really curious about is [there is] a lot of discussion around, when these kind of restorations happen, what does it mean for the [Black] filmmaker? Is it a smooth process to unearth something?

ZiD: Yeah, I could only speak for myself. I mean I'm very happy that I'm in such good company with other particularly other Black women filmmakers like Bridget Davis who you helped bring Naked Acts.7 Thank you very much again for that wonderful film.

Ayo's8 film “Alma’s Rainbow” [and] well even Charlie9 with an “Annihilation of Fish” to some degree. I think part of it is that there is this deep satisfaction in knowing that your work is evergreen meaning that even though you made something that was in the 90s, it can still be appreciated by audiences, full stop period. So I think that's the gift of the restoration / rejuvenation for me is that what you did back then was worthwhile and it's still relevant or it can be appreciated by audiences today. [That] has gotten me through the hard work of doing the rejuvenation as I call it.

MC: Why do you call it a rejuvenation and what are the differences between the original release and this one?

ZiD: I say it's a rejuvenation because it's better than the original, different than the original. [The] main differences are three things. The obvious one, which is that the picture is so much better in 4K. I'm very glad we shot it in 16 mm film because that's a stable form for cinema and we know we can make copies of that negative. But now with 4K, the clarity in terms of the visual details is so much nicer.

A couple of things I can point out for people is that [both] of my actors are dark-skinned African-Americans and in some sections of the film, particularly in the “L” Train [citation] sequence, we did that gorilla style so we didn't have lighting in any of those scenes [but] now with the restoration you can really see the difference. And then with the archival photographs, you can actually see some more of the detail because with the rejuvenation, we were able to clean up those photographs. And in some cases we're able to zoom in just a tiny bit. …And then the sound. The clarity has renewed the picture. The sound was completed on a 16 mm optical track And I spent months working the night shift with a group in Chicago called MaestroMatic to do the sound design because that's my favorite part of the film making process.

We designed the soundtrack with deaf [and hard of hearing] people in mind so we did some experiments with sound so that we would push the sound to its loudest points because in some instances Michelle said that her experiences of sound seem to be heightened when she could put her hand close to a speaker so she could feel the vibration of the music. We have sections that are really loud with the train or really loud with the Chicago house music that's in the film. Those are deliberate choices and we were able to kind of bump that up to its full levels with the rejuvenation.

And then lastly, and most importantly, I think what we did with the captions is really very satisfying. I was able to work with another hearing filmmaker Allison O'Daniel who did the film “Tuba Thieves” and it was at Sundance 2023. Allison collaborated with me to do more immersive captions for the film. We were able to have the music mostly in the upper left-hand corner of the frame and then the sound effects are over on the right and the dialogue is in the in the in the center of the frame sometimes, but one of the things that Allison taught me was that it was more it would be better for deaf and hard-of-hearing office audiences if the captioning was closer to the speaker who was actually talking so that if it's multiple characters in the scene, then the deaf or hard of hearing audience member would know who was talking because the captions would be as close to their body as possible. So it wasn't just in the center of the screen, it moves to different parts of the screen. And so that I think made it more immersive and available to the audience.

MC: Thinking about your filmography, you're such a visually innovative and transformative director. And I really want to know how do you maintain your creative spirit?

ZiD: Thank you. I think it's constantly being exposed to students because I have to keep up and that [informs] my practice. I'm teaching them, but they teach me also, and I've always been someone who wants to see new work. I [also] go to various film festivals just to see who the new makers are that are upcoming and watch their works to appreciate what they're doing. I think just constantly being exposed to as much film culture as you could get and and getting back into the practice of going to the movie theater and not just seeing it on my laptop; it's really important that we still have that movie going experience because there's just something magical about sitting in a dark room with a whole bunch of other people and experiencing what's on the screen in front of you… and Black folks we talk to the screen… I think that the magic of having somebody in the audience respond to something that you can identify really soothes my soul. It makes me feel good. In “Compensation” even though it's generally kind of a serious movie, there's moments of humor in there. Some of them are brought by my own biological brother, Kevin Davis who plays the Tyrone character in the contemporary section. So that it is basically a continuation of our practices as LA Rebellion filmmakers to use people from our community to make our films. So in my case, and in several LA Rebellion filmmakers…We use our family members in the films. So I think that it's kind of important that we involve our communities in the film making process in whatever way. We do it and I think that also keeps me going and reinvigorated.

On the “Compensation” rejuvenation, I have two daughters and my daughters helped [with the process.] They both sat down with me and watched the film painstakingly over a few weeks time and like we we worked on saying what the music was, what it could be and they did an amazing job. I could not have done it without them because they had the knowledge of music, but I had the knowledge of film so we could we could speak to each other across those lines and and come up with something that would let audiences know what the music is but not bludgeoning them with like saying, well, you need to feel this way.

MC: “Compensation” is such an act of love because, your creative partner and life partner as the writer, then involving your family in the rejuvenation. I mean just all of this is just so significant and it shows in the work.

ZiD: Yep, Mark Arthur Chéry, that's my screen writer. I still cry sometimes when I watch “Compensation” because of the beauty of the words that he wrote in the letter from Malika to Nico, when she lets him know what's going on with her and then also with that letter from Arthur to Melendi. I've seen the film thousands of times probably but it still makes me very excited and happy to see that as well. I'm so grateful really.

The rejuvenated “Compensation” is now playing in arthouse cinemas across the country with Janus Films. Find showtimes here. Watch “A Powerful Thang” and “Cycles” on Black Film Archive now.

In its fullness, hooks defines oppositional gaze as films that look through Black life through a Black lens.

From a 1992 interview :-)

“End of the world” being a phrase that is thrown around often. I remain an optimist.

The interview has been edited for clarity.

The director Ayoka Chenzira.

so blessed to see this article right after leaving the silver spring screening and q&a for compensation with zeinabu and the lead actor, michelle, and marc, the writer. 😭❤️ my second watch in the last week. excited to read but had to comment!!

Wow. Another gem of an interview. This all sounds so fascinating! How I wish “Compensation” was being screened in/near my city?! This work, like all of the works, featured in the archive sounds both beautiful and of vital importance. Damn, I feel smarter having just read the interview. Lol.