For All We Know and For All We Cannot Yet See

The role of the artist in Black cinema, life, and Palestine

Growing up in the American South I thought often of the work belabored by matriarchs that shaped my home and heart. There was the mending, tending, and plowing work that kept the home in order; the heavy are the hands that bring life into each stitch, ditch and pitch that kept our families together; and the invisible thread of care, tenderness, and courage that held our hearts together. With their tender and firm grasp of the world, I learned we had to take care of what we know (community, love, family) and tend to what we can not yet see (the kaleidoscopic wheel of life’s possibility—danger, change, and transformation).

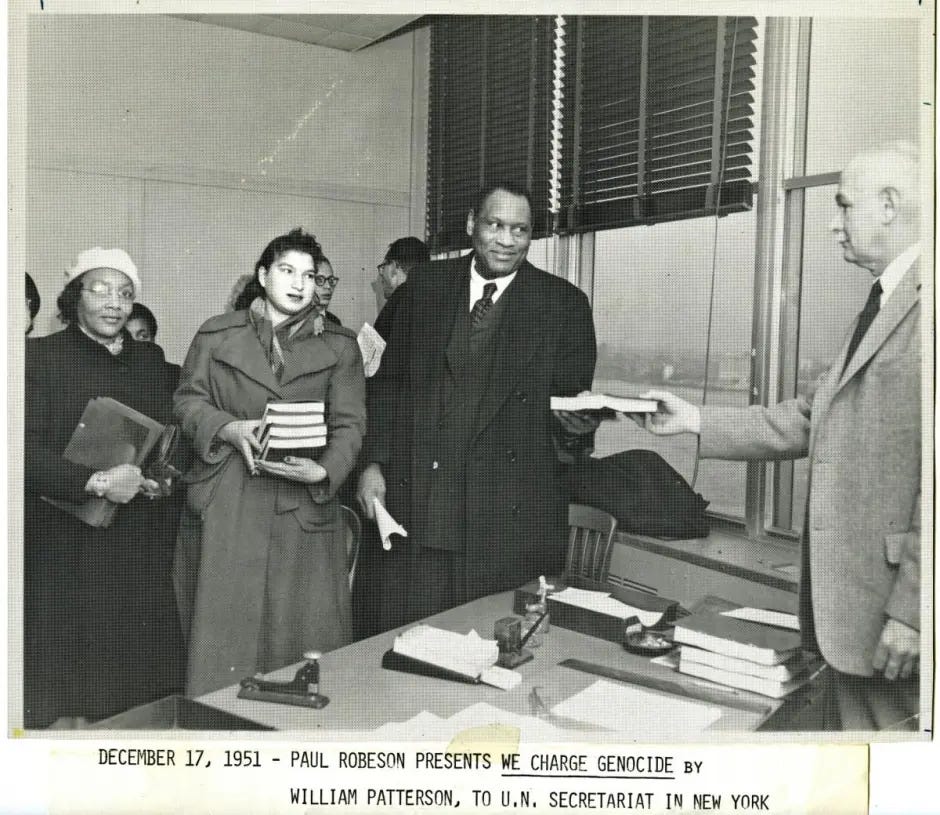

This impulse is reflected in Black cinematic images on screen and among the pioneers who constructed and reconstructed the craft. Oscar Micheaux, pioneering Black director and producer, said “moving pictures have become one of the greatest revitalizing forces in race adjustment.” Micheaux knew then that we must stake our own claim in cinema’s development as an art form, propagandic tool, and cultural mainstay. In the ever-pressing contentious question of ‘how must we represent the race with this art form?’ is the desire for cinematic imagery to not simply be reactionary to the ‘race problem’ but a tool of social change that showcases what is invisible to us.1 To this point, activist and the star of Micheaux’s 1925 film “Body and Soul” Paul Robeson agrees, saying “through my singing and acting and speaking, I want to make freedom ring. Maybe I can touch people’s hearts better than I can their minds, with the common struggle of the common man.”

In this lens, cinema can be understood as a tool of not only spectacle or entertainment but a marking of time, possibility, change and transformation bearing witness to the common person. A tool– if deployed with intention– of endless discussion and intervention; a testimony to the change of social order and an unbinding of the ties of colonial, capitalistic, and racist fantasies.

As filmmaker and writer Toni Cade Bambara writes in her essay “Language and the Writer,” “Can the planet be rescued from the psychopaths? The persistent concern of engaged artists, of cultural workers, in this country and certainly within my community, is, What role can, should, or must the film practitioner, for example, play in producing a desirable vision of the future? And the challenge that the cultural worker faces, myself for example, as a writer and as a media activist, is that the tools of my trade are colonized. The creative imagination has been colonized. The global screen has been colonized. And the audience—readers and viewers—is in bondage to an industry. It has the money, the will, the muscle, and the propaganda machine oiled up to keep us all locked up in a delusional system—as to even what America is.”

As it has been said and repeated, it is clear that the task of the artist is to make what others can not yet see radically visible. As spectators and culture workers, our task is to render that invisibility into our own language to share with our communities and provide them with the tools to continuously share with others. Art infinitely renders the world anew if our eyes are open to what others cannot yet see as we connect with ourselves, our homes, and our community. The actions of artists, cultural workers, and deep-read spectators are the tending labor that shapes the world and brings about collective transformation. The role of the artist in a revolution is to make the revolutionary power of humanity clear and enticing.

Though the task of the artist may paint portraits of romanticism, of clear-conscious individuals who have never fallen prey to the trappings of institutions, power structures, or social order, that seldom is reality. Artmaking, as Toni Cade Bambara said clearly, has been put in bondage to an industry that demands artists' silence in exchange for the will to continue practicing freely. The task ahead of us— filmmakers, writers, spectators, painters, cultural workers, and everyone in between— is to have the courage to act. We must ask ourselves: is our artmaking, our lives, our creative practice dedicated to justice or what is right for only us as an individual?

With this understanding, the question of the role of artists of conscious in relation to Palestine is clear: we must have the courage to imagine, believe, and fight for Palestinian liberation. If we are called to action from the mass graves we’ve seen, we must do all we can to fight for the living with the belief that what is done is not final.

Knowledge does not make us inherently courageous— we can know every fact and dictate a history– but courage, as necessary in this moment and as history reflects, is quite simple: Palestinians are facing a genocide and we must do all we can to act on their behalf. Perhaps courage is the point awareness becomes movement and movement makes way for transformation; to become a path of unlearning the conditioning that has been seeped into our consciousness about Zionism as a choice of morality and inevitability.

If the artist’s tool of choice is imagination, imagination is courage but only as far as we allow it to radically construct a new world and take others with us. Community is courage as it requires vulnerability and care to show up with intention. Love is courage if you allow it to transform you. Inspiration is courage if you allow it to help you imagine anew.

We have borne witness to Israel’s decades long genocidal war against Palestinian people and sought the comfort of words of others for what we cannot yet express. But, perhaps, we are all artists and must take our duties seriously. We’ve all had to ask ourselves–choose– where our allegiance lies, but the lack of choice remains one. I want to make clear that my only allegiance is to doing all I can to make a morally just world and continuously listen and act as that definition changes and expands.

If you’re looking for a place to begin, may I suggest the growing list of films about Palestinian liberation and freedom Palestine Film Index; the Black magazine Hammer & Hope’s Palestine issue; and GazaFunds.org.

P.S. - I will be back latter this month with underseen Black queer films for Pride month.

I don't want to negate the fact that racist imagery does construct how Black people are seen on screen or the fact that there is a history to be told with Black cinema's formation being, partially, in response to 'Birth of a Nation’ but this tension is precisely why I think making Black life visible to other black people — which what was what race films (early black cinema) was for — remains critical to my point.

Great essay, makes me think...but also despair. What can we do? Art, film, and literature are necessary and helpful but seem passive. The protests seem misdirected. Writing and calling the same useless politicians that fail at running the country? And what of our own everyday dramas and traumas?

Wow. Prescient as always. I’ll have more to add to the dialogue once I’ve digested. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

In solidarity